These promotions will be applied to this item:

Your Memberships & Subscriptions

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet or computer â no Kindle device required.

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera, scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

Colour:

-

-

-

- To view this video, download

Audible sample

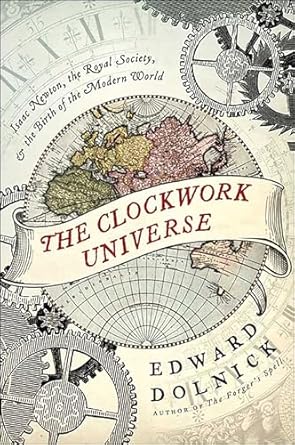

Audible sample The Clockwork Universe: Isaac Newton, the Royal Society, and the Birth of the Modern World: Isaac Newton, the Royal Society, & the Birth of the Modern World Kindle Edition

ÂéķđĮø

In the late seventeenth century, chaos and disease reigned. Streets overflowed with filth and the murder rate was five times higher than it is today. Sickness was divine punishment, astronomy and astrology were indistinguishable, and the world's most brilliant, ambitious, and curious scientists were tormented by contradiction. They believed in angels, devils, and alchemy, yet also believed that the universe followed precise mathematical laws that were as intricate and perfectly regulated as the mechanisms of a great clock.

The Clockwork Universe captures these thinkers as they wrestled with nature's most sweeping mysteries. Award-winning writer Edward Dolnick illuminates the fascinating personalities of Newton, Leibniz, Kepler, and others, and vividly animates their momentous struggle during an era when little was known and everything was newâbattles of will, faith, and intellect that would change the course of history itself.

"Dolnick's book is lively and the characters are vivid." âThe New York Times Book Review

"A free-for-all of ideas in a character-rich, historical narrative." âThe Wall Street Journal

"Dolnick writes clearly and unpretentiously about science, and writes equally well about the tumultuous historical context for these men's groundbreaking discoveries: the English Civil War, the Thirty Years' War, and in 1665 and 1666 respectively, the Black Plague and the Great Fire of London. Dolnick also offers penetrating portraits of the geniuses of the day, many of them idiosyncratic in the extreme, who offer fertile ground for entertaining writing." âPublishers Weekly

- LanguageEnglish

- PublisherHarper Perennial

- Publication dateFeb. 27 2024

- File size6.8 MB

In this series (1 book)

Customers who read this book also read

Product description

Review

âDolnickâs book is lively and the characters are vivid.â â New York Times Book Review

âA character-rich, historical narrative.â â Wall Street Journal

âEdward Dolnickâs smoothly written history of the scientific revolution tells the stories of the key players and events that transformed society.â â Charlotte Observer

âAn engrossing read.â â Library Journal

âDolnick . . . writes clearly and unpretentiously about science, and writes equally well about the tumultuous historical context . . . [He] also offers penetrating portraits of the geniuses of the day, many of them idiosyncratic in the extreme, who offer fertile ground for entertaining writing. [Dolnick] has an eye for vivid details in aid of historical recreation, and an affection for his subjects . . . [An] informative read.â â Publishers Weekly

âA lively account of early science. . . . Colorful, entertainingly written and nicely paced.â â Kirkus Reviews

âDolnick furnishes a fine survey introduction to a fertile field of scientific biography and history.â â Booklist

â[Dolnick] offers penetrating portraits of the geniuses of the day . . . who offer fertile ground for entertaining writing. [He] has an eye for vivid details in aid of historical recreation, and an affection for his subjects . . . [An] informative read.â â Publishers Weekly

From the Back Cover

In a world of chaos and disease, one group of driven, idiosyncratic geniuses envisioned a universe that ran like clockwork. They were the Royal Society, the men who made the modern world.

At the end of the seventeenth century, sickness was divine punishment, astronomy and astrology were indistinguishable, and the worldâs most brilliant, ambitious, and curious scientists were tormented by contradiction. They believed in angels, devils, and alchemy yet also believed that the universe followed precise mathematical laws that were as intricate and perfectly regulated as the mechanisms of a great clock.

The Clockwork Universe captures these monolithic thinkers as they wrestled with natureâs most sweeping mysteries. Award-winning writer Edward Dolnick illuminates the fascinating personalities of Newton, Leibniz, Kepler, and others, and vividly animates their momentous struggle during an era when little was known and everything was newâbattles of will, faith, and intellect that would change the course of history itself.

About the Author

Edward Dolnick is the author of Down the Great Unknown, The Forgerâs Spell, and the Edgar Award-winning The Rescue Artist. A former chief science writer at the Boston Globe, he lives with his wife near Washington, D.C.

Product details

- ASIN : B004GB1TTA

- Publisher : Harper Perennial

- Accessibility : Learn more

- Publication date : Feb. 27 2024

- Edition : Illustrated

- Language : English

- File size : 6.8 MB

- Screen Reader : Supported

- Enhanced typesetting : Enabled

- X-Ray : Enabled

- Word Wise : Enabled

- Print length : 421 pages

- ISBN-13 : 978-0062042262

- Page Flip : Enabled

- Part of series : The Clockwork Universe

- ÂéķđĮø Rank: #89,863 in Kindle Store (See Top 100 in Kindle Store)

- #18 in History of London

- #52 in Scientist Biographies (Kindle Store)

- #83 in History of Science eBooks

- Customer Reviews:

About the author

Edward Dolnick is the author of Down the Great Unknown and the Edgar Award-winning The Rescue Artist. A former chief science writer at the Boston Globe, he has written for The Atlantic Monthly, the New York Times Magazine, and many other publications. He lives with his wife near Washington, D.C.

Customer reviews

Top reviews from Canada

There was a problem filtering reviews. Please reload the page.

- Reviewed in Canada on August 29, 2017Verified PurchaseI bought this as a gift for a science lover who says it is very interesting. He is fairly educated in this area, but says the book adds incredible detail and background into scentific history. I, being a complete science novice, also read a bit of it and found it fantastic. In sum, this book is great for both science enthusiasts and beginners. Highly reccommend!

- Reviewed in Canada on October 22, 2015Verified PurchaseIt's a good read, Dolnick demonstrates how religion played a huge part in scientists view of the universe, probably slowing progress in science by many years regretably.

- Reviewed in Canada on November 1, 2019Verified PurchaseImmensely enjoyed the book. Recommend to anyone interested in science or history.

- Reviewed in Canada on October 5, 2017Verified PurchaseVery entertaining and informative.

- Reviewed in Canada on January 4, 2015Authors of many (most?) of the great works of non-fiction make brilliant use of the basic elements of a narrative. That is certainly true of Edward Dolnick and of The Clockwork Universe. Its setting is London in the 1660s. As for its cast of main characters, they include Robert Boyle, Lord Brouncker, Edmond Halley, Robert Hooke, Isaac Newton, Christopher Wren, and other members of the "The Royal Society," founded in November 1660 when granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II. They and their contemporaries (notably Gottfried Leibnitz) "stood upon the shoulders" of other major "players" in years past, such as Galileo, Kepler, Descartes, and Francis Bacon. The dramatic tension that energizes Dolnick's lively narrative is the result of their struggles to read God's mind. 17th century scientists' perception of God as a mathematician who had written His laws in code. Their task was to find the key. In essence, their efforts serve as this book's plot. Newton serves as the chief protagonist. Dolnick's focus "is largely on the climax of the story, especially Newton's unveiling, in 1687, of his theory of gravitation." But there are also other major breakthroughs and "false trails" that serve as subplots.

As he explains, "at some point in the 1660s, a new idea came into the world. The notion was that the natural world not only follows rough-and-ready patterns but also exact, formal, mathematical laws. Though it looked haphazard and sometimes chaotic, the universe was in fact an intricate and perfectly regulated clock." Nature's laws were vast in range but few in number; God's operating manual filled only a line or two. For example, when Newton learned how gravity works, "he announced not merely a discovery but a 'universal law' that embraced every object in creation...God was a mathematician, seventeenth-century scientists firmly believed. He had written His laws in a mathematical code." Separately and in collaboration, the scientists saw themselves as code breakers.

Here in Dallas near the downtown area, there is a Farmer's Market which several merchants offer fresh slices on fruit as samples. In that same spirit, I now provide a few brief excerpts to suggest the thrust and flavor of Dolnick's style.

On the importance and significance of mathematics: "To the Greek way of thinking, the everyday world was a grimy, imperfect version of an ideal, unchanging, abstract one. Mathematics was the highest art because it was the discipline that, more than any other, dealt with eternal truths. In the world of mathematics, nothing dies or decays." (Page43)

On the Royal Society's motto: "Science today is a grand and formal enterprise, but the modern age of science began as a free-for-all. The idea was to see for yourself rather than rely on anyone else's authority. The Royal Society's motto was 'Nullius in Verba,' Latin for, roughly, 'Don't take anyone's word for it,' and early investigators embraced that freedom with something akin to giddiness." (58)

On Aristotle's legacy: "It was Galileo more than any other single figure who finally did away with Aristotle. Galileo's great coup was to show that for once the Greeks had been too cautious. Not only were the heavens built according to a mathematical plan, but so was the ordinary, earthly realm...This was a twofold revolution. First, the kingdom of mathematics suddenly claimed a vast new territory for itself. Second, all those parts of the world that could [begin italics] not [end italics] be described mathematically were pushed aside as not quite worthy of study. Galileo made sure that that no one missed the news. Nature is 'a book written in mathematical characters,' he insisted, and anything that could not be framed in the language of equations was 'nothing but a name.'" (93 and 94)

On relativity: "Galileo not only defended Copernicus against his critics but, in the course of making his argument, devised a theory of relativity. Three centuries before Einstein's version, Galileo's theory proved nearly as hard for common sense to grasp...Nothing is special about a motionless world. Smooth, steady motion looks and feels exactly the same as utter stillness. The strongest argument against Copernicus -- that he began by assuming something that was plainly ridiculous -- was invalid." It is noteworthy that Galileo reached his far-ranging conclusion "by means of the humblest experiments available." (171 and 172)

Today, relativity could be explained by noting that a glass of water on a table in a dining car of a train traveling 200 mph behaves the same as a glass of water on a kitchen table in a residence. In fact, Einstein once observed, "If you can't explain an idea to a six year-old, you really don't understand it."

When concluding his brilliant examination of a group of scientists who set out to read God's mind and what they learned, Dolnick reiterates the fact that, in all the important ways, Newton was not like other men. "Perhaps we would do better to acknowledge the gulf than try to bridge it. At Cambridge, Newton could occasionally be seen standing in the courtyard, staring at the ground, drawing diagrams in the gravel with a stick. Eventually he would retreat indoors. His fellow professors did not know what the lines represented, but they stepped carefully around them, to avoid hindering the work of the lonely genius struggling to decifer God's codebook."

This is one of very few books in recent years that, as I reached the final chapter when reading it for the first time, I regretted that it would soon end. Now on to Edward Dolnick's previously published works.

- Reviewed in Canada on March 15, 2011I cannot praise this book enough; in fact, reaching the end of it was a big disappointment for me - I wanted more. I have read a great many books on the history of science over the years and, from my experience, very few are as much of a pleasure to read as this one. The author focuses mainly on science in the 1600s but he does touch upon a few developments from earlier times. The book's subtitle mentions Isaac Newton and the Royal Society. Unfortunately, this does not do justice to the book's content. Although the Royal Society is discussed sporadically and Sir Isaac and his accomplishments are the main highlights of the last third, the book includes so much more, e.g., other Renaissance giants such as Galileo, Kepler, Brahe, Leibniz, Hooke, Boyle, etc., the religious fervour of people back then, plagues and other disasters and their superstitious interpretations, etc. But where this book shines the most is through its clear, captivating and friendly prose. The author guides the reader through the logic that Newton and Leibniz went through when they developed calculus; he goes over Newton's reasoning as he was developing his theory of universal gravitation; and, all the while, emphasizes how important God was to these great minds.

Although this is a book about science, it is mainly about its history and as such readers who may be math-phobic have nothing to fear. Reading this book should be a most enriching experience for anyone. Even the most avid science buff who has read it all a number of times before would likely not help being riveted to this book nevertheless, as the pages turn by themselves; I sure was.

Top reviews from other countries

N MalikReviewed in the United Kingdom on May 26, 2024

N MalikReviewed in the United Kingdom on May 26, 20245.0 out of 5 stars Great book, written with flair

Verified PurchaseIntriguing and interesting.

Engaging from beginning to end.

I just wish the narrative was a bit more linear in timeline as it get a bit confusing what event occurred before or after another event.

-

RFOGReviewed in Spain on November 11, 2012

RFOGReviewed in Spain on November 11, 20123.0 out of 5 stars El tÃtulo lleva a confusiÃģn sobre el contenido

Verified PurchasePodrÃamos decir que este es la continuaciÃģn de The Genesis of Science ya que empieza mÃĄs o menos donde acaba ÃĐste.

Lo comprÃĐ pensando que era una historia de la Royal Society inglesa, pero en lugar de ello y pese al tÃtulo, se centra mÃĄs bien en el perÃodo histÃģrico que va desde CopÃĐrnico hasta mÃĄs o menos la muerte de Newton, y sobre todo ambientado en la cultura anglosajona, como no podrÃa ser de otra forma.

En comparaciÃģn al anterior, ÃĐste estÃĄ mejor escrito y cubre el perÃodo de forma mÃĄs o menos temÃĄtica y luego cronolÃģgica, desde los aspectos sociales de la ÃĐpoca, pasando por los mÃĐdicos, de ciencias naturales y finalmente matemÃĄticos y fÃsicos.

Sin aportar nada nuevo sobre el perÃodo, sà que puede ser un buen punto de entrada para comprender el nacimiento de la ciencia tal y como la conocemos hoy en dÃa.

Clay GarnerReviewed in the United States on October 29, 2017

Clay GarnerReviewed in the United States on October 29, 20175.0 out of 5 stars âWhat follows is the story of group of scientists who set out to read Godâs mind.ââ

Verified PurchaseâGod was a mathematician, seventeenth-century scientists firmly believed. He had written His laws in a mathematical code. Their task was to find the key.ââ

This deep, unshakable, overriding âfaithâ in the mathematical creator, was the foundation for the scientific breakthrough.

âMy focus is largely on the climax of the story, especially Newtonâs unveiling, in 1687, of his theory of gravitation. But Newtonâs astonishing achievement built on the work of such titans as Descartes, Galileo, and Kepler, who themselves had deciphered paragraphs and even whole pages of Godâs cosmic code. We will examine their breakthroughs and false trails, too.ââ

âAll these thinkers had two traits in common. They were geniuses, and they had utter faith that the universe had been designed on impeccable mathematical lines. What follows is the story of a group of scientists who set out to read Godâs mind.ââ (176)

This work does marvelous job of explaining the process that destroyed one world and then started another. Moreover, Dolnick paints clear portraits of the men who did it, and the strange (to us) religious motives that drove their lives.

Why should we, in this scientific/technological age, give any thought to this? Note . . .

âJust as Newton had discovered the laws of inanimate nature, so would some new thinker find the laws of human nature. A handful of rules would explain all the apparent happenstance of history, psychology, and politics. Better still, once its laws came to be understood, society could be reshaped in a rational way.ââ

This âfaithâ in human reason, human âscienceâ, surfaced in the French Revolution, and resurfaced in the Russian revolutions and drives much of the political/psychological/economic thought now.

âAmericaâs founding fathers argued explicitly that the success of the scientific approach foretold their own success. Free minds would make the world anew. Rather than defer to tradition and authority, the new thinkers would start from first principles and build on that sturdy foundation. Kings and other accidental tyrants would be overthrown, sensible and self-regulating institutions set in their place.ââ

Overthrowing tyrants was great! Installing Robespierre and Hitler was not!

(''Woodrow Wilson, on the campaign trail in 1912, told voters that it was time for the federal government to be liberated from its outmoded eighteenth-century scheme of checks and balances.''

''Government, Wilson said, was a living organism, âaccountable to Darwin, not to Newton.â Since no living thing can survive when its organs work against one another, a government must be free to adapt to its times, or else it will perish. The adaptation Wilson had in mind was to neutralize Congress and consolidate power in a vigorous executive.'' - âIlliberal Reformersâ by Thomas C. Leonard)

âIn the portrait of himself that he liked best, Benjamin Franklin sat deep in thought in front of a bust of Newton, who watched his protÃĐgÃĐ approvingly. Thomas Jefferson installed a portrait of Newton in a place of honor at Monticello. As they spelled out the design of Americaâs political institutions, the founders clung to the model of a smooth-running, self-regulating universe. In the eyes of the men who made America, the checks and balances that ensured political stability were directly analogous to the natural pushes and pulls that kept the solar system in balance.ââ

People are not machines, no matter how hard you you force them to become one.

âThe Constitution of the United States had been made under the dominion of the Newtonian theory,â Woodrow Wilson would later write. If you read the Federalist papers, Wilson continued, the evidence jumped out âon every page.â The Constitution was akin to a scientific theory, and the amendments played the role of experiments that helped define and test that theory.ââ

Well. . .

This work is outstanding presentation of the change from medieval world to modern.

How did it happen?

Why then?

Who responsible?

Key dates and events . . .

1543 Copernicus publishes On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres, which says that the planets circle the sun rather than the Earth

1600 Shakespeare writes Hamlet

1609 Kepler publishes his first two laws, about the paths of planets as they orbit the sun

1610 Galileo turns a telescope to the heavens

1619 Kepler publishes his third law, which tells how the planetsâ orbits relate to one another

1633 Inquisition puts Galileo on trial

1637 Descartes declares âI think, therefore I am,â and, in the same book, unveils coordinate geometry

1642 Galileo dies

1642 Newton born

1660 Official founding of the Royal Society

1664â66 Newtonâs âmiracle years.â He invents calculus and calculates gravityâs pull on the moon.

1674 Leeuwenhoek looks through his microscope and discovers a hidden world of âlittle animalsâ

1675â76 Leibnizâs âmiracle year.â He invents calculus, independently of Newton.

1687 Newton publishes the Principia, which describes âThe System of the Worldâ

1704 Newton publishes an account of calculus, after thirty years of near silence

Dolnick explains not only the men, but even more interestingly, the world (both physical and mental) in which they lived. Really provides glimpses into our past and what those key men overcame to bring modernity. For example . . .

âBut to judge the Principia by the accuracy of its predictions is to see only part of it. In a similar sense, you can admire Michelangeloâs Pietà as a gorgeous work of art even if you have no religious beliefs whatsoever. But to know what Newton thought he was doing, or Michelangelo, you need to take account of their religious motivation.ââ

This religious foundation of science is so. . .so. . .weird!

âNewton had ambitions for his discoveries that stretched far beyond science. He believed that his findings were not merely technical observations but insights that could transform menâs lives. The transformation he had in mind was not the usual sort. He had little interest in flying machines or labor-saving devices. Nor did he share the view, which would take hold later, that a new era of scientific investigation would put an end to superstition and set menâs minds free. Newtonâs intent in all his work was to make men more pious and devout, more reverent in the face of Godâs creation. His aim was not that men rise to their feet in freedom but that they fall to their knees in awe.ââ

Fascinating that Newtonâs impact is precisely the reverse!

Another important idea is the significance of the new abstract thinking. . .

âIn the history of science, abstraction was crucial. It was abstraction that made it possible to look past the chaos all around us to the order behind it. The surprise in physics, for instance, was that nearly everything was beside the point. Less detail meant more insight. A rock fell in precisely the same way whether the person who dropped it was a beauty in silk or an urchin in rags. Nor did it matter if the rock was a diamond or a chunk of brick, or if it fell yesterday or a hundred years ago, or in Rome or in London.ââ

This was a direct attack on Aristotle. Why?

âEven if a vacuum could somehow be contrived, why would anyone think that the behavior of objects in those peculiar conditions bore any relation to ordinary life? To speculate about what might happen in unreal circumstances was an exercise in absurdity, like debating whether ghosts can get sunburns.ââ

Seems obvious. Nevertheless, it is wrong! Galileo fought this error. . .

âGalileo vehemently disagreed. Abstraction was not a distortion but a means of seeing truth unadorned. âOnly by imagining an impossible situation can a clear and simple law of fall be formulated,â in the words of the late historian A. Rupert Hall, âand only by possessing that law is it possible to comprehend the complex things that actually happen.â

This change, this commitment to abstraction, started the road to modernity.

Dolnick writing for general reader, not scholars. Smooth, clear, pleasant and enjoyable. Closer to a historical novel than academic essay.

Twenty eight color photographs. Three hundred twenty footnotes, extensive bibliography and index.

(I also listened to the audible version. Excellent rendition. So pleasant and effective, I plan on returning. Great!)

EiticReviewed in the United States on March 22, 2011

EiticReviewed in the United States on March 22, 20114.0 out of 5 stars A World Changing Era Brought to Life - Worth Reading!

Verified PurchaseEven social science majors with the remnants of an inexplicable aversion to math, geometry, and calculus will find Edward Dolnick's book a fascinating account of modern science coming to life in the 1600s and setting the world on an explosive path to modernity. Dolnick brings together the science and the thinkers within the context of the religious and political world of the era. Philosophers and mathematicians had long been encumbered by religious, political and social barriers to free thought. In the unique period of history recounted by Dolnick, the utter brilliance of Newton and others crashed through the corrosive barriers of religious dogma. Religion and royalty became willing partners to their efforts. The start of modern science and remarkable progress in the understanding of universal laws emerged. That is the story that Dolnick recounts in a very readable form and enlightening manner. I wish that Dolnick's book had been available as required reading before I trudged through my obligatory math courses in undergraduate and graduate school. I would certainly have viewed mathematics differently. I now have a greater appreciation for the struggles of Newton and others to capture the knowledge that was essential for the creation of our modern world and our still limited understanding of the universe. If you are a math teacher or you have a budding mathematician in your family, The Clockwork Universe is a must read. Expect to enjoy it and to marvel at the story as it unfolds.